Gender research in One CGIAR: Where do we go from here?

That’s the question gender researchers from across CGIAR will attempt to answer when they come together for a virtual meeting this week. The questions below are meant to kick off the discussion on solidifying the research agenda for the new CGIAR GENDER Platform.

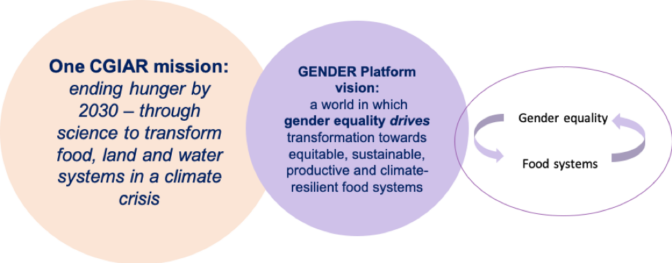

It is an exciting time for CGIAR and for gender research in CGIAR. We are making rapid strides toward One CGIAR, with its mission of ending hunger through science-driven transformation of food, land and water systems in the context of climate change.

The new CGIAR GENDER Platform will contribute to this mission by reimagining the CGIAR gender-research-for-development agenda. We envision a new era in which food systems transformation and gender equality reinforce one another, accelerating and amplifying benefits that are equitable, sustainable and lasting.

To realize this ambition, we need to sharpen our gender research priorities. While the GENDER Platform will build on several years of rich gender research, we now need to prioritize transdisciplinary and solution-oriented research to achieve tangible and substantive impact on social equity. The evidence we generate should be of practical value and help shape actions and investments in support of food systems transformation and gender equality.

I present here a list of six top-level research questions that I think are crucial to answer to achieve both the GENDER and the One CGIAR visions:

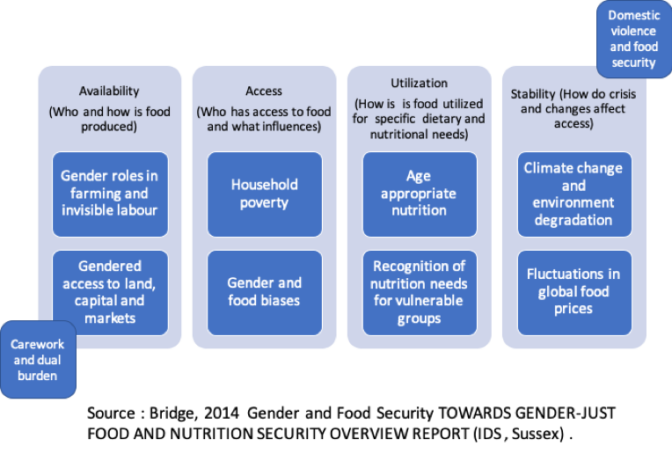

1. What are the gender dynamics in food systems that influence the four pillars of food security: availability, access, use and stability?

Women are considered the gatekeepers of the food system, yet they are nutritionally the most vulnerable, also across generations. In Penny Van Esterik’s words, “women are both vulnerable and powerful—victimized and empowered—through food.”

While CGIAR has been embracing a food systems framework to guide its work, we do not yet have a comprehensive understanding of how gender dynamics influence food systems. Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed additional fault lines in the relationship between gender and food security. It is time to systematically examine how gendered power relations influence food availability, access, utilization and stability. Our goal should be to design and test bundled interventions that provide effective and lasting solutions.

The framework of Bridge 2014 is helpful for thinking through gender dynamics in food systems.

2. How can we strengthen rural women’s engagement in labor markets?

We know that rural people working in informal agricultural labor markets and without land—many of whom are women—are the most vulnerable to climate, health, economic, political and security shocks. Again, the COVID-19 crisis has exposed how these groups, and the risks they face, are invisible in policy discourses and actions.

We need to systematically look at the evidence we have on gender in formal and informal rural labor markets, paying particular attention to women’s engagement and the implications for income, employment and vulnerability. We should pull out the evidence needed to stimulate gender-responsive policies and risk-reduction strategies that can contribute to women’s economic empowerment.

3. How can we ensure that women have equal access to decision-making on land and water systems?

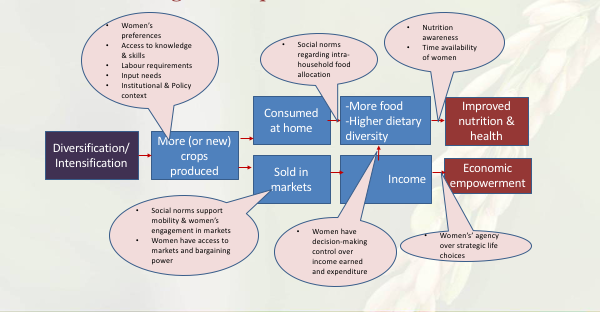

Understanding the land-water-energy-food nexus and developing strategies for sustainable intensification and diversification to overcome land and water constraints is gaining ground in CGIAR. But, the important gender dimensions of such strategies are not well understood. Synthesizing the data and evidence we do have can help us identify gaps and distill key messages that can influence policies and programs. We should invest in understanding how women’s collectives can drive changes in land and water governance as well as in decision-making, and we should investigate what works for strengthening women’s tenure and assets. These are critical questions to answer if we are to ensure that intensification and diversification do not result in additional burdens and labor for women, but rather in additional benefits.

Intensification or diversification of agricultural systems has strong gender implications.

4. How can we support women to engage in markets and entrepreneurship?

CGIAR has a rich tradition of research on women’s empowerment and has developed and promoted wide-scale application of tools such as the Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI). Now, women’s entrepreneurship is emerging as a key area that offers significant potential for economic empowerment. Going forward, we need to design and test strategies to support women to engage in markets, including through gender-responsive financial products and risk-reduction mechanisms.

5. How can we change the structural barriers and social norms that stand in the way of gender equality?

CGIAR entered the realm of research on gender transformative change in 2012 and began analyzing the social and gender norms that are the root causes of gender gaps to find effective and lasting solutions to bridging these gaps. The critical importance of women’s disproportionate burden due to unpaid care work and resulting time poverty has been acknowledged. We need to generate more evidence on the impact of this strain on their health and well-being, economic opportunities, participation in formal labor markets and ability to benefit from intensification strategies. However, we also still need to come to better grips with addressing structural barriers and influencing norms. Similarly on masculinities and engaging men as partners and champions in efforts to achieve gender transformative change. Understanding what drives gender transformative change, how to measure it and how to achieve it at scale is a relevant and urgent question to address.

6. How do we best measure the impact of gender research?

I would like to believe that we in CGIAR are past the stage of asking “why” we should do gender research, but rather are now asking “what” and “how” to best do it. Outcomes and impacts of social research are often intangible, have significant time lags and might not be quantifiable, just as the pathways to impact are very complex, context specific and dynamic. However, we do periodically face the question “why”, and therefore it would be worthwhile investing in methods and tools that allow us to unequivocally answer why gender research matters.

These six big questions might serve as a starting point for the CGIAR GENDER Platform’s new research agenda. To be successful, the research and synthesis efforts we undertake need to be underpinned by strong capacities, frameworks, approaches and tools, including on intersectionality, mixed (qualitative-quantitative) methods and big data. We must also remind ourselves that climate change, and other crises such as global pandemics, are major drivers of change in global food systems.

To get this right, we need to think as if there is no box. We need to forge unconventional and inter-sectoral alliances in research, academia and development to address the wicked challenges we face in agriculture and food systems today. Strengthening our own capacity—and that of our partners—to ensure uptake at scale of our cutting-edge, evidence-based solutions will be crucial to achieve equitable, sustainable, productive and climate-resilient food systems.

Dr. Ranjitha Puskur lead's gender and youth research at International Rice Research Institute and is a socio-economist.

Want to join our community? To engage in regular exchanges with colleagues and partners about the CGIAR GENDER Platform and related resources and opportunities, sign up for our online discussion group here. We look forward to your input!