Sparking gender transformative change: Rome-based Agencies and CGIAR share experiences

Guidelines launch article (FAO Photo)

During the launch of the ‘Guidelines for measuring gender transformative change in the context of food security, nutrition and sustainable agriculture’, a dialogue panel between a representative of the Rome-based Agencies and one from the ONE CGIAR system focused on the opportunities and challenges of assessing normative constraints to gender equality in agrifood systems.

The following is an excerpt of the panel discussion between Els Lecoutere, Lead of HER+, the CGIAR Initiative on Gender Equality, and Silvia Sperandini, Senior Consultant, Gender Equality and Social Inclusion at IFAD. The discussion was moderated by Elizabeth Burges-Sims, Deputy Director in WFP’s Gender Equality Office.

The text has been edited for clarity and brevity.

What activities are you and/or your partners working on to spark gender transformative change in the context of food security, nutrition and sustainable agriculture?

Silvia Sperandini, IFAD: IFAD has always been at forefront of promoting gender equality in rural communities with a focus on gender transformative and long-lasting results. Our conceptualization of gender transformative programming started a decade ago. We first defined a very precise gender marker system that is applied at design, monitoring and completion. We gave ourselves some specific targets: 35% of the IFAD project portfolio has to be rated as gender transformative at design, and 60% as fully gender mainstreamed or transformative at completion.

The focus on eliminating the root causes of gender inequality and promoting sustainable, inclusive and transformative change requires good practices at both operations and institutional levels. We invest a lot to ensure that the right technical support is provided during the whole project life cycle. Strong attention is also placed on the capacity development of colleagues, implementing partners, project staff and development experts who are involved in the design and implementation of our operations.

Another key ingredient is knowledge generation. The JP GTA plays an important role because FAO, IFAD and WFP complement each other as organizations, and we are working together on the development of guidance tools that are key for the design and implementation of our projects.

Over the years, some of our approaches and activities have resulted particularly transformative. Many of you may already know the Gender Action Learning System (GALS), but during the JP GTA Learning Route recently organized in Malawi, we also saw other approaches implemented by IFAD-funded projects. These included Gender Dialogue Sessions and the Gender Transformative Ultra-Poor Graduation Model integrated with Household Mentoring, as well as Theatre for Development used with a gender transformative potential to address behavioural changes and discriminatory practices. With the JP GTA we have recently piloted the Financial Action Learning for Sustainability (FALS) in Malawi and Cerrando Brecha in Ecuador. We need programmes like the JP GTA to pilot new gender transformative approaches and activities that can further boost our standard operations.

Els Lecoutere, CGIAR HER+ Initiative: Currently, several research initiatives and programmes within the CGIAR are working towards gender transformative change. To do this, they implement gender transformative approaches or address structural constraints to gender equality in agrifood systems in other ways.

As a first example, in our HER+ Gender Equality Initiative, the work package “Transform” seeks to address discriminatory social norms. It identifies normative constraints, designs measurement tools, and co-designs innovations such as gender transformative approaches to address these constraints. This focuses mainly on informal institutions and unwritten social norms at different value chain nodes in agrifood systems.

For example, the multidimensional gender social norm index looks at normative constraints at different spheres of influence - household, community and systemic levels – and aims to unlock women's agency by addressing constraints related to mobility, labour division, leadership, decision-making, and participation in markets and value chains. It also tries to uncover and challenge power relations embedded in norms.

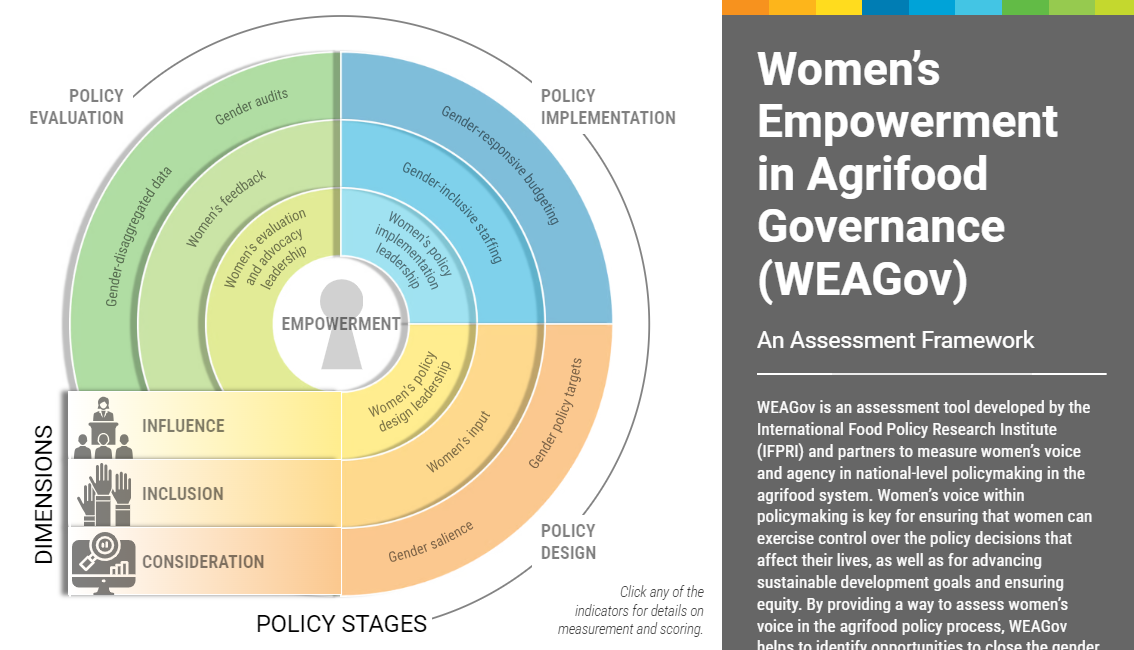

Another example is the Women's Empowerment in Agrifood System Governance Assessment Tool (WEAGov) that has been designed for policymakers, stakeholders and researchers to collaboratively identify parts of policymaking processes where women's voices are missing and to find ways to open opportunities for meaningful inclusion. This addresses the formal institutions and power relations, mostly in the macroenvironment.

WEAgov.

Have you found measuring gender transformative change challenging in your programmatic work? And if so, how?

Els Lecoutere, CGIAR HER+ Initiative: From a research and measurement perspective, the construct validity of indicators for gender transformative and norms change has been a challenge. For instance, in large-scale surveys, we capture support for wife beating, for childcare to be a mother's responsibility, for jobs to go to men as a priority, or for women as leaders. Do we really measure what we intend to measure there? Do we capture norms? Do we capture results of norms? Or do we capture a mixture of norms and some societal phenomena? Also, can we use those different data points in time as panel data for measuring norm change or transformative change? I think these Guidelines help to reflect upon that.

Also, in many cases, we measure outcomes related to empowerment, assuming that only if interventions are transformative, we would be able to see positive changes in empowerment. What is sometimes missing are these pathways of incremental and catalytic changes that form a theoretical backdrop for that.

The last challenge is that gender transformative change is not always measured as a process, and as a process that happens at different scales and speeds. The Guidelines are helpful in visualizing and being explicit about that.

Silvia Sperandini, IFAD: When we try to monitor the changes on the ground, we sometimes realize that we don't have the right qualitative and quantitative indicators, structures, tools and methods. Even if we do have them, we struggle to introduce them as part of existing monitoring and evaluation systems.

Our project staff find it difficult to measure the different dimensions of gender transformative change as they consider it particularly time- and resource-consuming. Conducting elaborate annual outcome surveys on complex aspects such as agency, power relations, and formal and informal social institutions is perceived as costly.

Another challenge is connected to the lack of a proper baseline and the need to conduct diagnostics on social norms that will help us to understand the context. Due to a lack of resources foreseen at the design stage, this is not always easy.

An additional challenge relates to the structure of monitoring and evaluation systems. Having gender sensitive M&E systems is something we should not take for granted. Data available on beneficiaries is usually sex disaggregated but does not always report on age or other socioeconomic characteristics of the target groups. This makes it difficult to assess the effective outreach of our interventions and the changes enabled by beneficiary type, by poverty status, age or ethnicity. Only with proper and complex M&E systems can we really get a better sense of the impact achieved.

More information: