We also carefully considered the need to go beyond measures of economic achievement, to also include other types of collective achievements, such as increased self-confidence and participation, and members’ satisfaction with groups. Such data can help shed light on what empowerment means to the women in those groups. The project teams—working with us throughout review, framework development, and project instrument development—succeeded in capturing this kind of data to varying degrees, and confirmed the need for such questions in future instruments they or other researchers may develop. For example, adding self-assessment questions about internally defined objectives and how these are determined can make those future tools more insightful.

Effectively capturing the group’s voice can also be tricky. Individual measures of collective agency have the benefit of being more standardized, conventional, and easier to gather—with fewer logistical complexities (e.g., assembling groups and deciding on who speaks for the group). MAGNET collected data from focus group discussions with group leaders as closed-ended questions, where only consensus answers were recorded. This enabled the project to collect more group-level indicators and helped triangulate results from the individual-level surveys, but may have masked differences of opinion within the leadership or failed to unearth other members’ perspectives. Metaketa’s approach was to measure the group’s official achievement (i.e. whether the group successfully received a grant, as well as the objective quality of the grant application).

All-purpose tool still out of reach, but framework useful

While crafting a universally applicable instrument remains elusive, the data that each project collected revealed common aspects that can be standardized to measure collective agency.

For example, there was great commonality in the data collected about group structure and dynamics (e.g., presence of bylaws, mission statement, record keeping, gender composition, and leadership). This kind of data could provide a useful reference for other studies. Other questions can uncover gendered constraints to participation that can then be addressed (e.g., questions about provision for transport, childcare and food at group meetings).

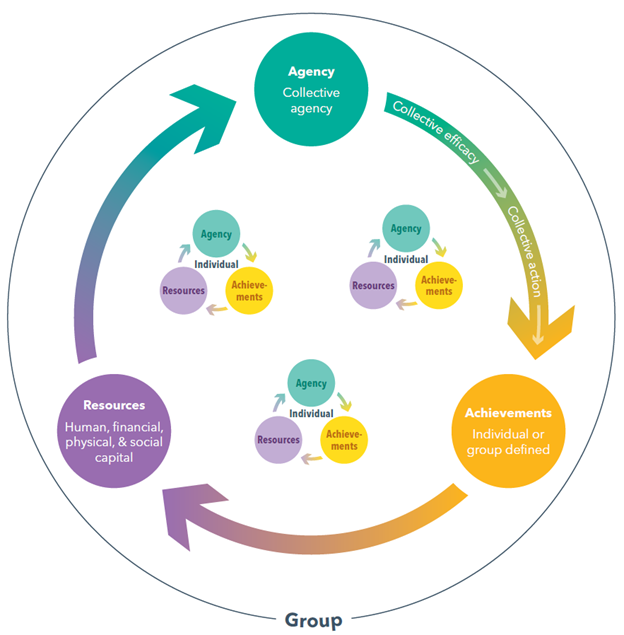

The framework provides a way of thinking through a theory of change for how:

- collective resources facilitate or constrain collective agency

- collective agency can be translated into achievements through collective efficacy motivating collective action

- those group achievements can build resources that, in turn, enable further collective agency

Combined with characteristics of individual respondents and of the groups, measures of these concepts can address researchers’ and practitioners’ questions about what types of women or men are able to exercise voice and agency in different types of groups; and how group composition, organizational structures, and decision-making processes affect collective agency and effectiveness.

For people studying group-based collective agency for research or project impact assessment, our framework, definitions and set of tools offer a useful starting point for thinking about what to measure.