Challenges collecting pro-WEAI data in climate-affected Nandi County, Kenya

United Nations SDGs 5 and 13 are to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, and to urgently combat the impacts of climate change, respectively, by 2030.

Kenya has not yet achieved gender equality goals due to challenges such as entrenched cultural norms which discriminate against women; limited access to social, economic and physical resources for rural women; and gender-based violence.

Climate change only exacerbates these challenges, making it essential that climate action intentionally reduces gender inequalities and increases women’s resilience capacities and agency. Tools to measure women’s empowerment in agriculture are essential to monitor progress toward SDGs 5 and 13, and to design and implement low-emission development projects and policies which contribute to these goals.

Understanding women’s empowerment in Nandi, Kenya’s Living Lab for People

The Living Lab for People (LL4P) in Nandi County, North Rift Kenya, seeks to support local innovations aligned with low-emission development by collaborating with multiple stakeholders. It is being piloted through CGIAR’s Low-Emissions Food Systems Initiative. Designing and integrating a gender-responsive framework is one of the foundational principles of the LL4P.

To inform such a framework, we set out to determine the status of women’s empowerment in Nandi County, women’s and men’s preferred strategies to build climate-resilience, and the perceptions and norms surrounding their participation in innovation processes. We collected project-level Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (pro-WEAI) data and additional qualitative data to inform the LL4P about inclusivity gaps in the county and to provide guidance on how to incorporate social inclusion in upcoming activities. The activities include:

- developing the innovations assessment framework

- creating awareness of the LL4P

- issuing a call for innovations

- scaling accepted innovations

Together with Kaimosi Agricultural Training Centre, Nandi’s LL4P host, we conducted the survey in six subcounties (n = 253 farming households).

The pro-WEAI provides a metric which can be used to measure the impact of agricultural projects on women’s empowerment and the degree of gender parity within households. For our study, we made some adjustments to the pro-WEAI questionnaire:

- emphasized value chains which are especially important in Nandi County (dairy, tea and vegetable)

- removed one module and some sections of two other modules for brevity (already identified as possible cuts in the original pro-WEAI questionnaire)

- added a section on experiences with and perceptions of climate change, as well as adaptive capacities. The climate change section consisted of three intrahousehold submodules that will be essential in understanding the relationship between empowerment levels and adaptive capacities in women and men farmers in Nandi County.

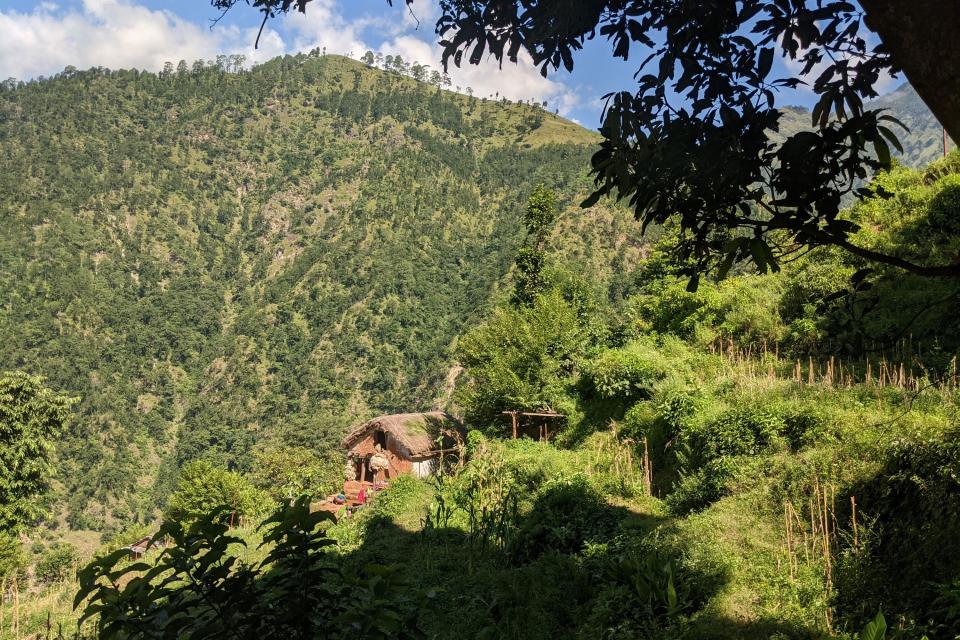

A farmer and his wife welcome a data collection team to their household in Kapkangani Ward (May 2024)

The field team consisted of myself and eight women and men enumerators who were responsible for collecting data. The team went through a six-day pro-WEAI training in May 2024. The team worked with Ward Agricultural Officers—government representatives under the Ministry of Agriculture who work directly with local farmers—who communicated with respondents before the interviews and located households for data collection. They also helped with replacements where respondents were not available on the days of data collection. The team completed data collection by the end of May 2024.

Challenges and lessons we learned about collecting the pro-WEAI data

Although we managed to collect the pro-WEAI data according to our schedule, we did face several challenges worth highlighting. The first rather mundane challenge concerned the weather. We were aware that fieldwork would take place during the rainy season, but were still confronted with logistical obstacles because of heavy rains. Hours were spent pushing our vehicles through the mud and sourcing people to come to our rescue. This affected everybody’s motivation and perseverance. We came to understand the importance of not only anticipating, but also mitigating weather-related disruptions—for instance, by choosing more deliberately which roads to travel and which to avoid. We needed some level of flexibility regarding both timing of fieldwork and sampling to mitigate that risk of weather-related disruptions.

A day in May after a storm in Kemeloi/Maraba Ward highlighting the challenges of unpredictable weather conditions.

The second challenge was about the sensitive nature of some topics in the survey. Women and men in Nandi County do not openly discuss topics such as gender-based violence, decision-making and ownership of assets in the household. These topics made many respondents, and some of our enumerators, uncomfortable. Most women respondents hesitated to respond to these questions, and some asked to consult their husbands. Some enumerators hesitated posing questions on these topics. We learned that it is important to understand the norms and cultures of respondents when designing a study and to discuss these issues in training before collecting data. Practice through role-play is a good way to familiarize and ease enumerators into sensitive topics, allowing them to learn how to anticipate and solve challenges that arise while they conduct surveys.

Third, the duration of the interview was long. Even when a woman and man in a household had previously agreed to do the interview, some of them got impatient and left the interview location after noticing how long it took their spouse to finish the survey. As a result, for some of the households we ended up talking to only one respondent. When this first respondent was a man, this led to a “null interview” according to WEAI requirements. Apart from designing shorter surveys, providing realistic time estimates to interviewees about surveys is important as well. For WEAI questionnaires, it is important to prioritize women for interviews, and to schedule separate interviews for the spouses of a household so that no one has to wait for the other during data collection.

The fourth challenge I experienced on a more personal level. As a young woman navigating my first professional job, I was leading the entire field operation, including the logistical preparation and planning, the training and the data collection itself. My identity as a young woman, not from the region, and not speaking the local language (Kalenjin) presented gendered challenges. I was responsible for critical decisions, but encountered resistance on several fronts. My team and drivers had issues taking instructions from me, wanting to take full control of planning and management—and even threatened to stop the exercise when I protested. I overcame these challenges after seeking guidance and support from my senior colleagues, whose involvement was instrumental in my gaining acceptance, eventually leading to successful implementation.

Self-awareness about gender discrimination is also required

In many parts of Kenya, it is still unusual for women—particularly young women—to make decisions for men or to take on leadership roles. When planning fieldwork or even stakeholder engagement, it is paramount to realize that societal expectations and discriminatory gender norms not only play out among the people we are researching, but also in our own research teams and in interactions with local people. When we talk about creating awareness about gender discrimination and social exclusion, we therefore should not forget to be more self-reflective about our own organizations, ourselves, our colleagues and other direct partners.

Gender inequality is still rife in rural Kenya. We need to anticipate this and find ways to respond that empower our own staff, and serve as examples and role models for other stakeholder interactions. My experience in this exercise was exciting and I hope to have contributed to normalizing young women taking on leadership roles.