Who claims the rights to livestock? What we learn from discrepancies in wives’ and husbands’ reports

Photo: K. Dhanji/ILRI

Photo: K. Dhanji/ILRI

Control and ownership of assets, including livestock, are key for women’s empowerment and gender equality, but we have little intrahousehold data about this. Using separate interviews with wives and husbands to explore these issues, we find that the rights over livestock are often held by different members of the household and that women and men in the same households report different patterns.

Owning assets—such as livestock—greatly influences women’s and men’s livelihood options, can provide resilience in the face of shocks, and is central to women’s empowerment. Research also shows that for rural women in low- and middle-income countries, livestock is often easier to acquire and maintain control over than land or financial assets.

Collecting data about who owns what types of livestock, and who has the rights regarding livestock and their products (like eggs, milk and meat) is important to understand the nuances of gendered patterns of livestock ownership.

However, data on the different types of assets women and men own and control remain limited. While some progress has been made in collecting and disseminating individual-level information on land and financial assets, there is insufficient information about women’s ownership and rights over livestock as evidenced in FAO’s 2023 report on The status of women in agrifood systems (Chapter 3, Livestock holdings).

Additionally, the traditional approach of asking the (usually male) household head is inadequate when it comes to understanding the complex, gendered patterns of ownership and the bundle of rights over assets—such as who manages the asset and who profits from the use of assets.

In our recent research, we analyzed the intrahousehold gender patterns of livestock ownership and looked at how husbands and wives responded to questions about their rights over different types of livestock. We use intrahousehold survey data collected by FAO as part of the Global Strategy for Improving Agricultural and Rural Statistics (GSARS).

This Ugandan husband and wife in Kiboga may have very different ideas about who owns the pig and its meat. Photo:ILRI/Danilo Pezo

Gathering intrahousehold data let us analyze the complexities of gendered ownership and rights over livestock

Two features of these data provide insights into husbands’ and wives’ livestock ownership in the study area. First, the survey asks questions to both wives and husbands (from 275 households) about the full bundle of rights over livestock—such as ownership rights, management rights and fructus rights (the rights to the benefits from the asset).

Each spouse was asked whether she or he currently owned (either exclusively or jointly) any animals of each type of livestock. Managers were defined as the individuals responsible for the financial aspects of the livestock and for ensuring the proper care and feeding of animals, including by supervising others who cared for the animals; not who provided the labor. Fructus rights were proxied by who made decisions about the use of livestock and their byproducts (such as eggs, milk, or meat) for home consumption and the market.

Second, we collected data separately and privately from both husbands and wives, rather than using the more common approach of interviewing the holder of the farm (usually the male household head). This meant we could better understand who was carrying out the different activities within the agricultural household, in addition to the gendered patterns of livestock ownership and rights.

Women’s ownership of animals does not guarantee their full rights over those animals

The information we gathered on multiple rights to livestock gave a clearer picture of women’s asset holdings. Various factors, including intrahousehold dynamics and social norms, may shape women’s rights to livestock, and claiming ownership does not necessarily translate into full rights over the animals.

While we found no statistically significant differences in the incidence of husbands’ and wives’ ownership of various types of livestock, we did find that ownership does not always confer other rights. People also hold rights without claiming ownership.

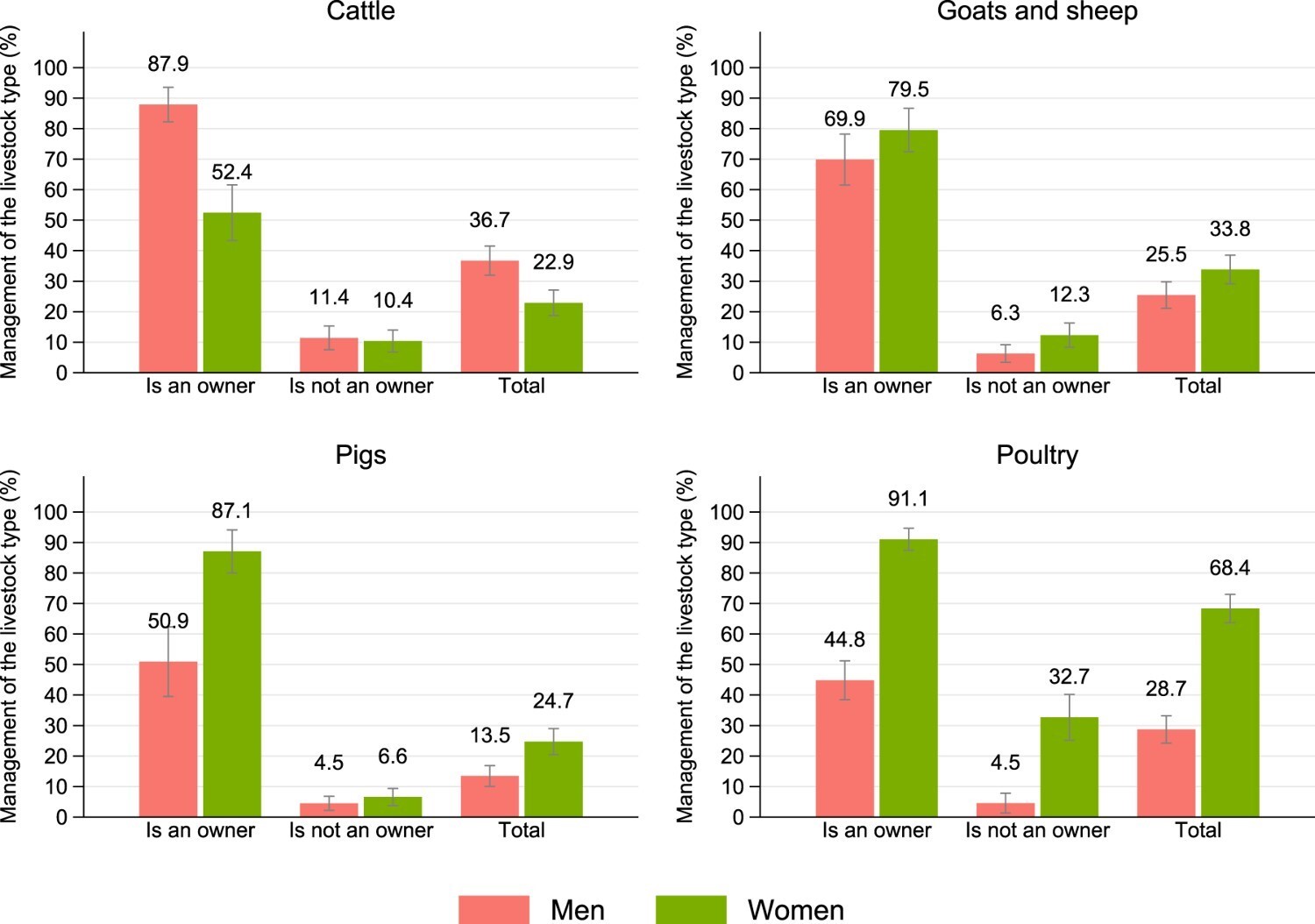

- Slightly more than half of women cattle-owners also manage cattle compared with nearly 90 percent of men cattle-owners. However, women who own other livestock types—including goats and sheep, pigs and poultry—were more likely than men owners to manage these animals (figure 1).

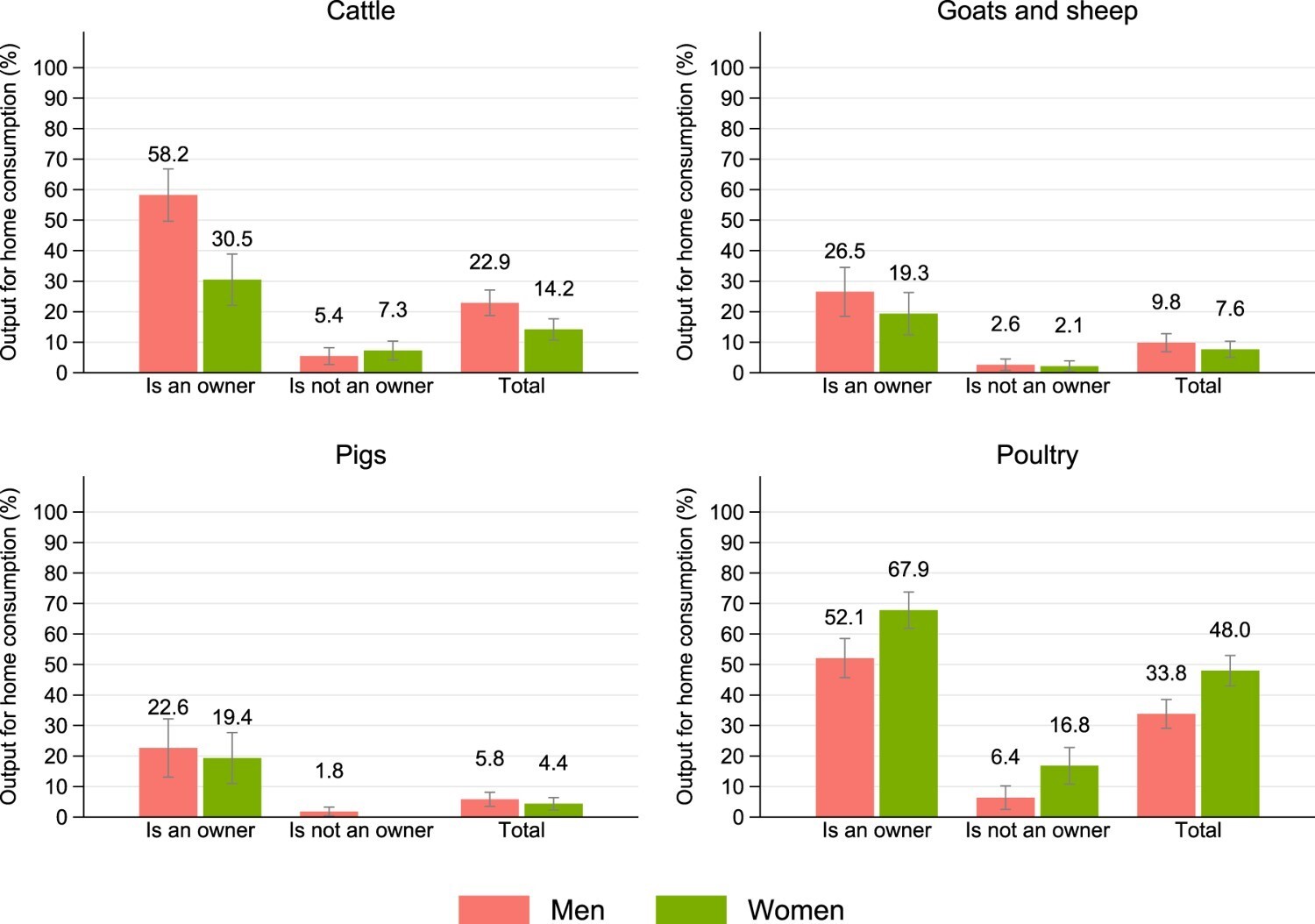

- Moreover, more husbands than wives reported fructus rights over cattle, goats, sheep and pigs—regardless of whether they are owners—but the reverse was true for poultry (figure 2).

Figure 1. Livestock management by gender, ownership status and livestock type

Figure 2. Fructus rights by gender, ownership status and livestock type

Our results revealed discrepancies between spouses’ reports of livestock ownership and rights

Interviewing both wives and husbands also enabled us to identify and analyze discrepancies in the responses of spouses regarding the number of animals in the holding and who holds the rights.

Discrepancies may be random errors or due to information asymmetries, but they can also provide insights into cases where rights to livestock are contested as well as ‘asset-hiding’ behavior.

During the piloting of the survey, field staff noted that some respondents were holding animals at another household, raising the question of whether spouses may be ‘hiding assets’ from each other. Some respondents hold animals at other households—though the numbers are generally low—and some respondents claim they own livestock although their spouse does not report them as an owner, which suggests some ‘hiding’ of livestock. This finding is consistent with literature that suggests that men and women hide financial assets.

There are also seemingly nonrandom discrepancies between women and men over the rights to livestock. For instance, wives tend to report having more involvement in decisions over the sale of milk and the use of earnings than their husbands’ reports reveal, which may indicate that women are selling milk without their husbands’ knowledge.

While the work on the bundle of rights over land is extensive, this study shows that it is also important to understand how the bundle of rights over livestock are held within households. The study also reminds us that it matters who is asked to complete the questionnaire, for the fullest understanding of gender patterns of ownership and other rights over assets.